Gluten–it’s an essential component in the structure and texture of baked goods as we know them. Gluten is predominately found in wheat and, to a lesser extent, in barley and rye. What is it? Well, it’s a protein – or more technically speaking, it’s a group of two proteins bonded to form a network. This protein network gives structure and function to doughs and batters. The two little proteins that constitute the gluten network are called glutenin and gliadin. The network of gluten these proteins form is what gives dough its elasticity (ability to retain its shape) and plasticity (ability to be molded, as in clay) that makes baked goods so unique and amazing.

Here’s how it happens: when water is added to flour, glutenin and gliadin are able to move more freely and form bonds with other glutenin and gliadin molecules they encounter, thereby creating a network of protein (that’s gluten!). Working the dough or batter by kneading or stirring helps encourage bonding, and strengthens the gluten network. Some baked goods require a lot of gluten formation, like bread and pizza dough; others require minimal formation of gluten, like cake and muffins. That is why any bread recipe will call for extensive kneading, whereas cake and muffins are stirred only enough to moisten the dry ingredients. This is all for the sake of gluten formation!

Let’s look closer at that example. When making bread or pizza dough, you’re typically instructed to “work” or “knead” the dough. This thorough mixing of the flour and water results in an extensive gluten network that creates a strong, expandable structure that can hold lots of air during rising, yields a baked product that is sturdy enough to allow for heaving toppings or sandwich contents without falling apart, and gives us bread’s delightful crust. In contrast, tenderness is the goal when it comes to cake and muffins. For these recipes, you’re typically instructed only to stir the batter enough to moisten the ingredients. This minimal mixing of the flour and water limits the ability of gluten to form, which allows the finished product to have a much softer bite and be more tender and crumbly (see the Muffin Method).

The photo below depicts an under-beaten, a correctly beaten, and an over-beaten muffin. You can see the lumpy, dense texture of the under-beaten muffin on the left. Its shiny top is caused by undistributed egg. The center muffin is correctly prepared, and looks normal. The muffin on the right is over-beaten, resulting in an over-abundance of gluten. This allows the steam that escapes during cooking to form large tunnels (called tunneling), which caused this muffin to buckle and collapse. The excess gluten in the right-hand muffin also yields a smoother, stiffer crust, which is not typically desirable in a muffin.

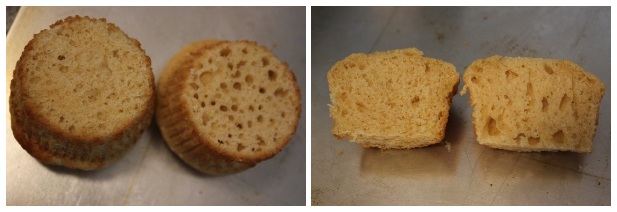

Take a look at these cross-sections of two muffins. The one on the left in both photos is prepared properly, and the one on the right is over-beaten. You can clearly see the tunneling in the over-beaten muffin, both from the bottom and the side views.

But there’s more to gluten formation than just stirring! The type of flour you’re using matters too! Even among commonplace white wheat flours there are many alternatives – cake flour, pastry flour, all-purpose flour, bread flour, durum semolina (for pasta); the list goes on. What’s the difference between these wheat flour varietals? Gluten! Well, technically since gluten isn’t formed in significant amounts until water is added, let’s refer to it as protein. Each type of flour has a unique protein make-up, but at this point, it’s also important to note that the leftover (non-protein) portion of white wheat flour is chiefly starch, which provides the soft, moisture-retaining bulk of baked goods by gelatinizing around the gluten skeleton. Knowing that white flour is essentially a starch-protein blend comes in handy if you have the wrong type of flour and would like to make a substitution. (See the second take-away lesson below.)

Here’s a breakdown of the rough protein levels of these common types of wheat flours:

Cake: 7-8%

Pastry: 8-9%

All-purpose (US national brands): 11-12%

Bread: 12-13%

Durum semolina: 13%

But it’s not just as simple as knowing the approximate quantity of protein in these types of flour, although it is an important factor. An advanced baker must also bear in mind that the quality of protein can vary among these flours as well. For example, durum semolina flour, which is used in pasta making, does not contain significantly more protein than the average bread flour. Why differentiate? Because in durum semolina, the protein makeup skews toward stiffer, more brittle proteins like glutenin, which gives the perfect texture for pasta, dense with stiffer chew. In bread flour, on the other hand, the protein makeup slews toward softer, more flexible proteins like gliadin, which produce a better balance of delicate and strong with dough that’s more stretchy than brittle. Cake flour is unique in a multitude of ways: in addition to its low protein content, it’s also ground finer than all-purpose flour and it’s always bleached, which not only whitens the flour, but also tenderizes it and lowers the pH. If a recipe calls for cake flour, there’s more to it than just protein, and there’s no perfect substitute for it.

It may be interesting to note that even among all-purpose flours there can be some differentiation. For instance, if you use a regional brand of flour, particularly in the Pacific Northwest or the South, your protein content is often closer to 7.5-9.5% (as opposed to the typical 11-12%). This could explain why your niece in Portland could never get her bread to look quite the same as yours in Boston, even though she used your exact recipe. Similarly, if you dine in Europe, you’ll be sure to appreciate their crusty baguettes, but you might notice they make a lousy muffin. Why? They may use the same recipes as we do in America, but European wheat has a stiffer protein content(higher in glutenin) than our more delicate American wheats (higher in gliaden). So, even with the same recipes, we find it difficult to perfectly replicate their crusty breads and they find it difficult to mimic the tenderness of our muffins and other baked confections.

Take-away lessons:

First lesson- Knead your dough according to recipe specs. Kneading more or less will impact the amount of gluten formed and thereby impact your final texture and appearance. (This goes for stirring as well.)

Second lesson. Choose your flour wisely! If your recipe calls for pastry flour but you only have all-purpose, you know what the difference is! If you simply substitute all-purpose flour for pastry flour, you’ll have too much protein in your dough and your product will come out tough (unless of course you’re using a local brand from the South or Pacific Northwest). All is not lost, however. As I mentioned earlier, wheat flour is basically just starch and protein. So if the flour you have on hand has too much protein, you could substitute plain starch (corn starch will usually do just fine) for a portion of your flour to bring the overall protein content down. Alternatively, if your recipe calls for bread flour but you only have all-purpose, you would need to compensate by adding something called vital wheat gluten. This is basically gluten that’s been separated from regular flour. Most vital wheat gluten is 70-85% gluten. Making adjustments yourself to the protein content of your flour is not likely to be very precise, as each brand will differ somewhat in protein content to begin with. However, it’s a great trick to have up your sleeve in a pinch. For example, I might employ the technique of substituting starch for a portion of my flour if I had a brownie recipe that consistently came out a little dry or lacking in tenderness. Instead of buying pastry flour, I could just tweak the flour to be tenderer by using ingredients I already have on hand. (Of course, there are other factors that can impact tenderness too. Click here to see a troubleshooting chart.)

And that’s it! You completely control gluten formation in your baked goods by selecting the proper flour and by working it the proper amount. Of course, there’s always more to be said on this subject, so read on for a few extra tips!

Additional gluten-taming tips:

Using whole wheat instead of white: Whole wheat flour varies in protein content more than white flour. It can contain anywhere from 11-15% protein. However, the bran acts as a physical barrier to gluten formation in the dough and therefore will result in denser products with less ability to rise. You can compensate for this by using additional leaveners, and by allowing half of the flour used in any whole-wheat recipe to be white. Another thing to note about whole wheat flour is that it contains fats that are normally removed in the processing of white flour. These fats are prone to rancidity (producing off flavors and smells), and as a result, whole wheat flour in general has a much shorter shelf life than white flour. Protecting your whole wheat starch from light and heat exposure can slow down this process. Therefore, it’s recommended to keep your whole wheat flour in the refrigerator to prolong its shelf life.

How gluten affects leavening: As any protein cooks, it denatures and hardens (think of an egg hardening from a liquid to a solid in the frying pan). Gluten is no exception to this rule. The heat from the steam and the oven together cause gluten proteins to denature and harden, forming the skeleton of bread. The elasticity and plasticity of the dough allow the mixture to stretch enough to accommodate the expanding steam (thereby leavening), but retains enough of its original structure to prevent the bubbles from bursting before they are set. If that were to happen, your loaf would collapse!

A nutritional note: The methods for controlling gluten formation outlined in this article are meant to relate only to how gluten impacts food, not how it impacts your body. If you are on a gluten-free diet, you should continue to avoid wheat, barley and rye products altogether. Always consult your doctor before making major changes in your diet.